Color It

by Sheldon C. Wesson

- The Wessons' publications were among the top examples of letterpress printing. In a series of three articles for the March, May, and July 1978 American Amateur Journalist (the Official Organ of the American Amateur Press Association), Sheldon Wesson explained how to use color.

Lives there a printer with soul so dead who never to himself hath said: "That initial would look great in red."

That moment of truth -- indeed, of revelation -- comes to most amateur printers along about the fourth issue of the first thumbnail title. Your typical hand-press banger will by then think he has exhausted the possibilities of black text on white paper, or even colored stock, and will yearn for the Class that color imparts to the printed page.

And, typically, his first color effort is a red initial.

But before we discuss the agonies of the first red initial, let us look at color in the broader sense of the term. In a journal of even four pages, it is possible to introduce variations in the texture and color of the page without opening a tube of anything but good old job black.

White space, dingbats, rules and border, bits that bleed into the margins, anything that breaks up the solid gray of the basic all-text page appeals to the eye as a variation in the color of the printed page. In this way, the printer obtains the contrast in appearance which arrests the eye. For the goal in the setting of the solid-text page is an evenness of color and texture which allows the type to be read without disturbance to the eye, with a restfulness that favors easy absorption and understanding.

The ideal use of rules, white space, large initials, etc., is to signalize to the eye and brain that a change of pace or of subject is introduced.

Similarly, the ideal uses of color in small journals are to signal a change of pace, to underscore a mood, to flag attention.

What this means, in effect, is that in the small format of the amateur journal, color should not be used randomly or just for the sake of displaying color. It should serve a purpose. In the same way that word-limits of our small formats require that every word count, so the small format requires that every typographical device introduced into the page be designed to serve a purpose.

It is not enough to introduce a left-handed green wombat into an article on fireplaces just to show that we acquired that wombat dingbat at a recent auction. The eye, which has been reading about fireplaces, looks at the green dingbat, and the brain responds, "so what?"

Perhaps the worst -- and certainly the least meaningful -- use of color we have seen in amateur journals is the solid text page in color. The eye will not accommodate the affront, and both legibility and comprehension are reduced. If we accept the tenet that the primary purpose of the printed text page is to communicate, then we have come a long way toward appreciation that the use of color must enhance that communication.

As an aside, consider for a moment the complex uses of color, illuminated initials in early Bibles, whether manuscript or printed. They serve two purposes: First, to enhance in the reader the feeling of grandeur imparted by the words; and, second, to demonstrate the devotion of the artist. There is an exact parallel with religious buildings of all sorts: The lavishment of time, energy, talent, resources to decoration are intended to enhance the building's ability to inspire awe, as well as to reflect the devotion of the sponsors and their artisans.

Now, take the simplest printed page in a small amateur journal. It contains a poem about trees. The printer finds a cut of a tree and skillfully weaves the type into the illustration (or vice versa) and enhances the appreciation of the words. He goes a step further, and prints the tree in leaf-green. The reader will scorn the perfectionist who insists that it is awful to show the trunk and branches in green, for only the leaves are green and the wood is bark-brown or black. The reader's eye accepts the suggestion of the color and the brain approves.

This doesn't mean the printer must despair if he doesn't own a cut of a tree in the proper size. He can obtain the same general effect by printing a three-line initial in leaf-green: for the color green reinforces the word "tree" in title or text. Imagination offers other solutions. The title of the piece is "How Green My World." Print the word "green" in green. To print the entire title-line in green is simple, the easy way out, just a bit pedestrian.

I visualize a poem about a cardinal in a tree. A 6-point dot of bright red, worked into an initial letter or even strategically spotted into the text, conveys the total image.

Back to that red initial. Sure, use a red initial, if you must. It shouts, "Something new starting here!" It serves the purpose. But before you reach for the tube of red, read the text again. Would some other color complement the words better, and still convey the same "start here" signal?

The message: The small format of the amateur journal requires that we use color sparingly, to be meaningful as well as decorative

Color Presswork

Successful printing of small color spots into a page tests the amateur pressman's patience and care. Careless makeready and other forms of criminal sloppiness are often largely covered up when a black-on-white text page is printed by slight over-inking or the merciful attitude of the paper stock. But a new world opens up when the amateur attempts to print his first initial.

If I had to name the single greatest virtue for the color printer I would unhesitatingly choose Cleanliness.

A sloppy cleanup job of the black run will gray a dark red or blue that follows. Okay, who knows, who cares. But when you attempt to print yellows, oranges, pale pinks and other delightful tints, any shadow of black left on rollers, inkplate, any place, will gray your tints and, progressively through the run, produce mud.

If your rollers are pitted, forget delicate colors. Find excuses to use nothing but dark greens and navy blue. The pits will bleed and weep gray into your ink for 10,000 impressions, however much you clean them. Forget it.

Given a fair shake with the rollers, clean them lovingly until not a shadow of black will show up on a white rag. Clean the roller trucks, removing traces of grease. Clean the inkplate to mirror-beauty. Clean the edges of the inkplate and underneath. Old ink will migrate many inches for the privilege of polluting a bright yellow.

If the initial or cut to be printed in color has been used for black, or any other color at all, place the printing surface face-down in solvent-soaked paper or cloth for an hour. Last year's dark blue, barely visible and certainly dead down in the counter of the type, will emerge to haunt you after 100 impressions.

The newly-involved color printer will find that a full text form tends to cover up improper adjustments of rollers, and will often tolerate minor variations in makeready or the adjustment of impression screws. A small color spot will not.

Soft makeready will make crisp color spotting impossible. Too spongy. Bring the platen up so that the color spot can be printed with at most one sheet of press-board and one of newsprint (behind the press-board, naturally). A new tympan sheet, tightly drawn, will be essential.

Clean the feet of the color form. Wipe dust from the stone. Do everything you can to be sure that initial, word, or cut sits level in the chase.

Nothing looks worse than a socked-in initial or color spot that punches badly. Besides, it ruins the type. A platen that is not level will not only cause the color spot to print unevenly, but will wear, even crush, one edge or corner of type metal.

Rollers must be adjusted to kiss the printing surface lightly or slur and ghosts will appear on the edges of the color form. Stiff or tacky ink tends to reduce the problem; soupy ink tends to magnify it.

Good register begins at the very beginning. If the basic form -- presumably black -- has been fed carelessly, no amount of care in handling the color form will make up for the wandering first impression. Forget it. Tell yourself that you intended that no two sheets would look alike, so that each will be a collector's item. Tell yourself that no one will know about the variations because each reader will only see one copy. All that proves is that you are a good rationalizer but a rotten printer.

Tight immovable gauge pins are so basic that they don't need mentioning. Anything on the tympan-sheet which prevents the paper from sliding easily and freely against and up to the guides must be removed. If the paper has been cut with a blade which has a nick in it, the resultant ridge on the edge of the paper may prevent the sheet from sliding freely into place on the press.

Start with a trifle of ink. Small color forms need little. Perform your miracles of makeready and produce a level impression in perfect register. Then and only then add ink, sparingly. You can sometimes get away with over-inking a full-page form, but not a small color-spot. An over-inked 24-point initial will look like it has been printed with bubble gum instead of ink.

When the first perfect impression comes off the press, the color will make the page light up, sing, smile, even dance. Congratulations.

Color Mixing

The TV commercials extol the virtues of pre-mixed stuff which makes momma's cookies taste almost as good as if they'd been baked from scratch. Well, you don't have to manufacture your own inks, but you can manufacture your own colors. Better than scratch. Better than pre-mixed. Your very own colors.

There are commercial ink-mixing sets which offer the printer a thousand charted shades from half a dozen basic tubes, in measured proportions. They are great for the printer who has a run of 10,000. But for the half-teaspoonful of pale green the amateur needs for a run of a few hundred, these kits and formulas are useless. Pinhead variations in quantities of color affect the final shade in the small quantities which we need.

Buy all your inks of the same brand and type. That way, you will get the feel of how they interact with each other when they are mixed. All the advice in the world won't substitute for the experience of actually mixing.

A simple one-inch putty knife serves as well as more expensive tools for mixing. Keep it clean. Whistle-clean. A 6x6 sheet of plate glass is a good mixing table. (Some people use the back of a galley. Great if you like the effects of rust, dirt and other crud mixed in.) I use old white square bathroom tiles, which are easily cleaned.

You need a tube of a stiff mixing white, a strong yellow, red, dark blue and dark green. Everything proceeds from these.

Your mixing must always be done under incandescent light. Even so-called daylight fluorescent gives you a false effect.

Always start with the light color and add the darker one. Your yellow becomes orange with an amazingly tiny bit of red. Mix thoroughly, over and over, until every trace of the red has disappeared from knife, mixing surface and mixture. Otherwise, a dot of red will show up after 100 copies and change the whole tint on the press. Add color a drop at a time.

Some of the most attractive tints start with white. There is a lot of blue in commercial red, so that a drop of red makes interesting violet-lavender shades, for instance.

Start with a shade in mind and build toward it, from light to dark. Never the other way. You need a pound of yellow to cut a teaspoonful of red down to an orange. Understand that the ink will look different on your mixing-plate, different on the press, different on different types of paper. So prepare to experiment. Reach a shade that looks good on the mixing-plate and make a light fingerprint with a clean finger-tip on your paper. That'll give you a hint of what the impression may look like.

This procedure is primitive, unpredictable, wasteful -- but unavoidable, creative, satisfying. How else can you match that great goldenrod color in the scarf that Aunt Hattie gave Elizabeth for her birthday?

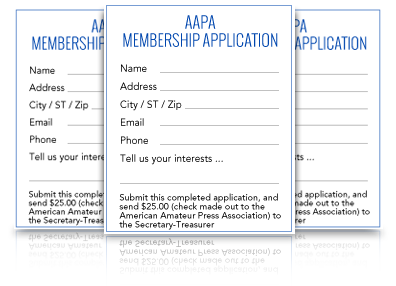

JOIN AAPA!

Become A Member!

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Amateur journalism is a unique activity. Amateur journalists publish journals on paper & online & come from many perspectives: from deluxe letterpress printed journals, to Xeroxed newsletters, to artistically designed cards and ephemera. We embrace the spirit of being amateurs – loving what we do for pure joy and not financial gain – while creating top quality journals, zines, and homemade publications.

Members receive ...

- The monthly bundle mailed via the postal service

- Access to the website and e-journals

- e-mailed updates

- Ability to publish your stories on AAPA

|

|